How to design in a crisis

On 17 April 2020, I received an urgent email requesting my attention as an in-house designer to work on a unique set of digital…

On 17 April 2020, I received an urgent email requesting my attention as an in-house designer to work on a unique set of digital experiences. It turned out to be a multi-billion dollar assignment from the Senior Vice President, Information Technology of Singapore Airlines to work with a taskforce to develop a digital solution that will raise funds for the company in the form of rights issues.

Background of the crisis

In case you’re wondering what prompted such a drastic action, it was largely due to the outbreak of COVID-19, which exploded in March 2020. Shortly after, governments started mandating border closures, resulting in a mad rush of travelers cancelling their flights.

Being on the grounds myself, I had experienced the initial hard impact when throngs of passengers lined up at the sales offices for immediate actions and refunds. What followed shortly after was financial instability, and the need to raise funds quickly. The company, like many other airlines during that period, was undergoing a crisis.

To make matters worse, as the task was time bound, the solution had to be ready in less than a month. Normally, such requests are achievable when there is a existing solution with clear requirements. In that particular case, we were building a whole new solution from scratch in a domain outside of our core business and very few past references.

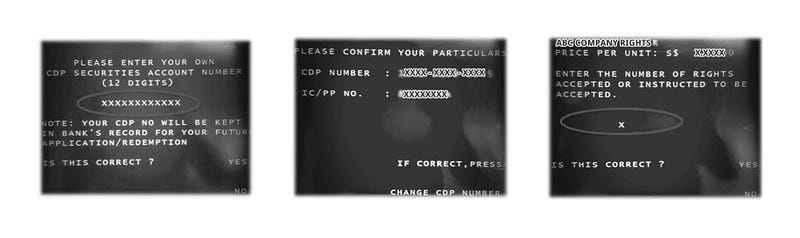

If this was not challenging enough, there another daunting task emerging. In previous implementations of the rights issue application, users are usually directed to the participating bank’s automated teller machines (ATM). A line of people can thus be expected queuing at ATMs. The user will then submit their rights issue application by interacting with the ATM.

Here’s the main problem: Singapore was undergoing a strict stay-at-home lockdown known as the Circuit Breaker, restricting movement of any Singaporean residents so as to reduce the spread of the virus in Singapore. It also produced the need to go contactless, which soon became one of the guiding key principles around subsequent COVID-19 digital initiatives.

At that point, the SIA taskforce could no longer solely rely on the incumbent method alone. They had to rethink a whole new user experience as a digital solution. And they had less than 30 days to go live.

Designing in Crisis

As UX designers, we thrive at solving problems through the creative use of our design skills and knowledge to deliver the best experiences for our users. But what happens when a problem becomes a crisis, when the stakes are high on criticality and urgency?

Suddenly, the design processes that we hone gets put to the test. And it quickly becomes increasingly difficult to apply. Should we conduct user research, collaborative sketching, wireframing and usability testing and design reviews, and if so, how could we have done it in a reduced amount of time? How do we then deal with the increasing complexity? How do we manage the emotions of various stakeholders, and yet uphold the experience felt by the user, who may not be directly affected by the crisis?

What happened in the next 30 days was an eye opening experience for myself as a UX designer working during a crisis. The following points below are based on my personal learnings from a specific crisis. Although I feel these points can be applied in other situations, they aren’t silver bullets that will solve every other crisis.

Perhaps some of these points may even be less impactful as compared to how other UX designers dealt with a similar situation. Nevertheless, I hope to share my experience with fellow designers, encouraging us that we have an important role, and by doing that to our best ability, we can achieve anything, no matter the toughest obstacles set before us.

1. During a crisis, think inside the box

Unlike other times when thinking outside of the box will be important to unlock new ideas, thinking inside the box is of utmost importance during a crisis. Identifying your constraints as quickly as possible is crucial to know the parameters of the design solution.

As the lead designer, I had to rule out any physical shared contact, yet consider the existing mental models, especially for users who had previously applied for rights issues, or are investment savvy. I also had to learn about the different types of shares that a user could apply for, and the legal and financial implications. Lastly, there was the technical requirements and limitations with our partnering bank.

As a result, I reenacted the user’s experience by finding instructions and ATM screenshot provided by blogs from helpful netizens. Further validations were made through experts and end user interviews. Only by gathering enough information and constraint could a designer internalize the depth of the problem and work out the optimal experience.

2. During a crisis, provide just-in-time UX

Sharing information and design deliverables in rapid small increments to business owners and developers makes the difference during a crisis.

In typical conditions, the design team tends to go in a design sprint, ironing out the kinks within the flows and constantly iterating on a set of agreed experiences with the product owner and developers before bringing it into an development sprint.

In a crisis, new information comes in every day. One moment, a new design requirement was created because there is a need to educate users on a new situation. Another moment, due to a change in the technical requirements, an alteration or a complete new set of designs has to be created.

I recalled shrinking my design deliverables to very small increments, and through regular reviews, design changes were made immediately and signed off. This way of working follows a concept known as just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing. Pioneered by Toyota in the mid 20th century, JIT moves materials through a continuous chain of processes as and when needed, reducing wasteful inventory increasing efficiency by reducing the lead time.

JIT UX means regular communication with the taskforce, being nimble to changes, and a heavily reliance on reusable components, only creating new components when absolutely needed.

3. During a crisis, the voice of the designer matters.

When time is limited, knowing when and how to speak as a UX designer will help to shape the eventual experience of the solution. The likelihood of others in a taskforce to jump with a solution is very high. This is very natural due to the quick assembling of a group of people who may be working together for the first time.

In my case, not only did i need to quickly acquaint myself to new colleagues in the taskforce, I was exposed to external collaborators, who may not have worked with a UX designer before. In one incident, I had an external collaborator with no technical or design background drafting up his version of 2 unique separate user flow. Had we continued with his version, there would be a higher abandonment and an unneeded rise in opportunity cost. Whilst his flow followed the conventional ATM flow, he lacked the exposure, experience and expertise of seeing another alternative of streamlining the flows into a single flow with 2 sub-sections.

It was at that moment that the taskforce has heard the voice of their designer, speaking up on an entirely new flow, and the need to create an essential feature that considered the user’s ability to apply for both shares at the same time. With no hard feelings, we proceeded with the proposed flows and features for the new solution.

Other occasions were calling for the need to create a new feature so that users can have a sense of affordance and familiarity to the abstract set of alphanumeric values they will receive as their right issues application. Despite the technical effort to build both logic and interaction, the end user benefits outweigh the cost, and the inputs of the designer were valued.

And there are times when the designer should listen to their stakeholders. The balance of what should be reused and what needs to be unique comes into play. I remembered a situation when I was too narrowed on providing the designs at speed that I did not consider the aesthetic treatment of a call to action (CTA) button at the entry point. It took another stakeholder who was equally close to the end user to voice out her thoughts. Through a discussion, I understood the rationale, and proceeded to turn the reusable component into something more appealing.

Speaking up on the user’s behalf is the designer’s responsibility at the seat of the taskforce table. Learning to listen and acting in humility is also part of that responsibility.

4. During a crisis, burn the ship.

There is a saying when someone burns the ship, it means that you are doing something that makes it impossible for yourself to turn back, especially if it is done willfully and without necessity.

As a designer, I tend to ruminate on how I could have created better designs. There could also have been many other elegant and better ways of creating the best experience for the user. With enough time and resources, such aspirations can be met. In a crisis, most designers should settle on “Good Enough To Move On”.

This does not mean that the designer should forsake standards and workmanship quality. Rather, it is a reminder for the designer in crisis mode not to backtrack on what was initial designed, and to proceed with the next set of tasks. It goes back to think inside the box and to come to a “good enough” experience for the user to complete the transaction.

And if there is complexity or uncertainty within the solution, work on the next best approach is to increase awareness and learnability. In this case, the design came in the form of FAQs, info banners, video explainers and tooltips.

5. After a crisis, learn and return back to normal.

Completing the design does not mean the company is out of the woods. The crisis is still in effect, and design fixes are likely to occur. In fact, because there were many firsts done in a short time, there were bound to be shortcomings.

One such example was our inability to conduct remote usability testing during a lockdown. The design team was not prepared for the crisis, partly due to the short amount of time and the lack of the right setup. Through the crisis, we realized that we had heavily relied on certain norms like on-site moderated usability testing. COVID forced us to relook at our process and tools. We learned as a team to deal with the situation, and subsequently did better with new tools on hand for the rest of the digital initiatives during COVID.

As time goes by, the solution would have served its purpose and the taskforce dissolves. Whilst there was good learnings during a crisis, learning to differentiate UX outputs between crisis and normal time is important. And that is because working in a crisis consumes a huge amount of cognitive load and energy from the designer. Once the situation is addressed, the designer should not to let the intensity of the previous work overflow and creep into your daily work. Resume back to proper time allocation, creativity and rigour. Learn and continue to move on.

With all that being said, there could be a chance that you may be experiencing a bigger crisis than what is being shared. Some of this could be personal or life threatening.

As mentioned earlier, there isn’t a single formula in dealing with every crisis. However, as we navigate through each crisis, we are able to learn, adapt and rise out of them becoming a little more resilient.

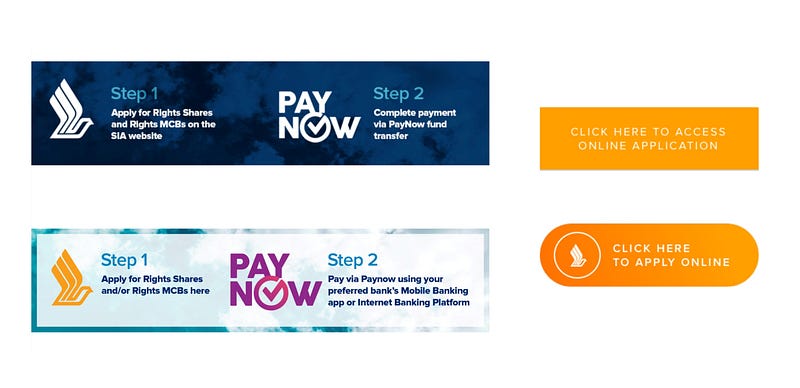

For Singapore Airlines, they have managed to secure the necessary funding in 2020 through the implementation of the first to market digital rights subscription and contactless payments solution in Singapore, with around 50% of users utilizing the digital solution. In 2021, the team was recognized by the industry with an award for best crisis management. But, more importantly, they now have a working solution that could be reactivated in should there be another crisis, along with the right processes and team in place.

Nobody likes to design in crisis. If given a choice, I will never want to go through such a crisis again. But as Winston Churchill would say, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” COVID-19 has inevitably humbled and shaped us as designers to become even stronger. I encourage fellow designers to rise up to their own crisis, and become even better practitioners.