The good, bad and ugly of a designer in the business world

Amid downsizing, designers must blend business thinking and embrace a “UX foxhog” approach to stay relevant

The good, bad and ugly of a designer in the crazy business world

This article is written for in-house designers in large corporate organisations. They deal with colleagues who don’t always share the same knowledge and skills. They also have to navigate difficult settings, especially when they are in the minority. Freelancers and designers from agencies may gain some insights into the life of an in-house designer but might not immediately identify with some of the examples.

But first, the ugly

Having complete design teams doesn’t seem to gel well in 2023 and 2024. We’ve seen the early layoffs in early 2023 when tech companies readjust their headcount in a post-pandemic world, but even towards the end of the year, companies continue to downsize. Perhaps the most telling sign is IDEO’s cutting of a third of staff and closing of offices as the era of design thinking ends. More recently, Spotify cut 1,500 jobs, equivalent to 17% of its workforce, to become leaner.

As reported in The State of UX in 2024, titled “late-stage UX,” Caio Braga and Fabricio Teixeira share the growing concerns of shrinking power and headcount in design. Whether downscaling comes from market conditions, manpower oversupply, or the recent advancement of AI automation, the future of design teams seems to be to do more with less.

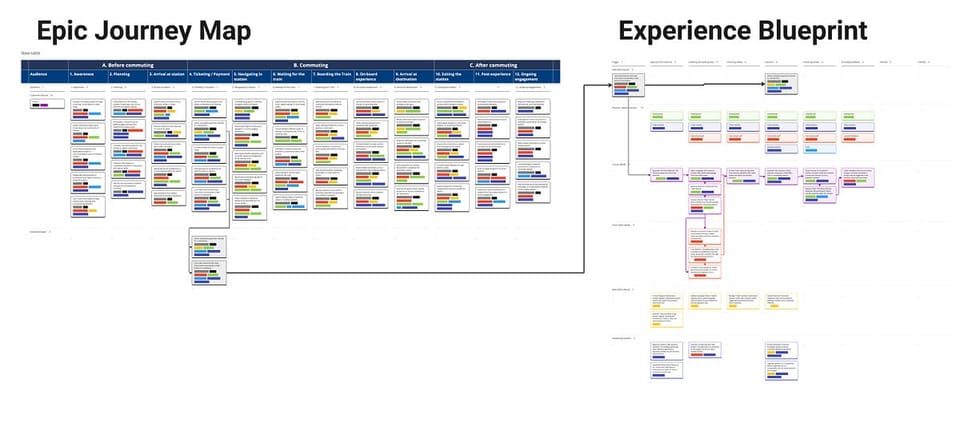

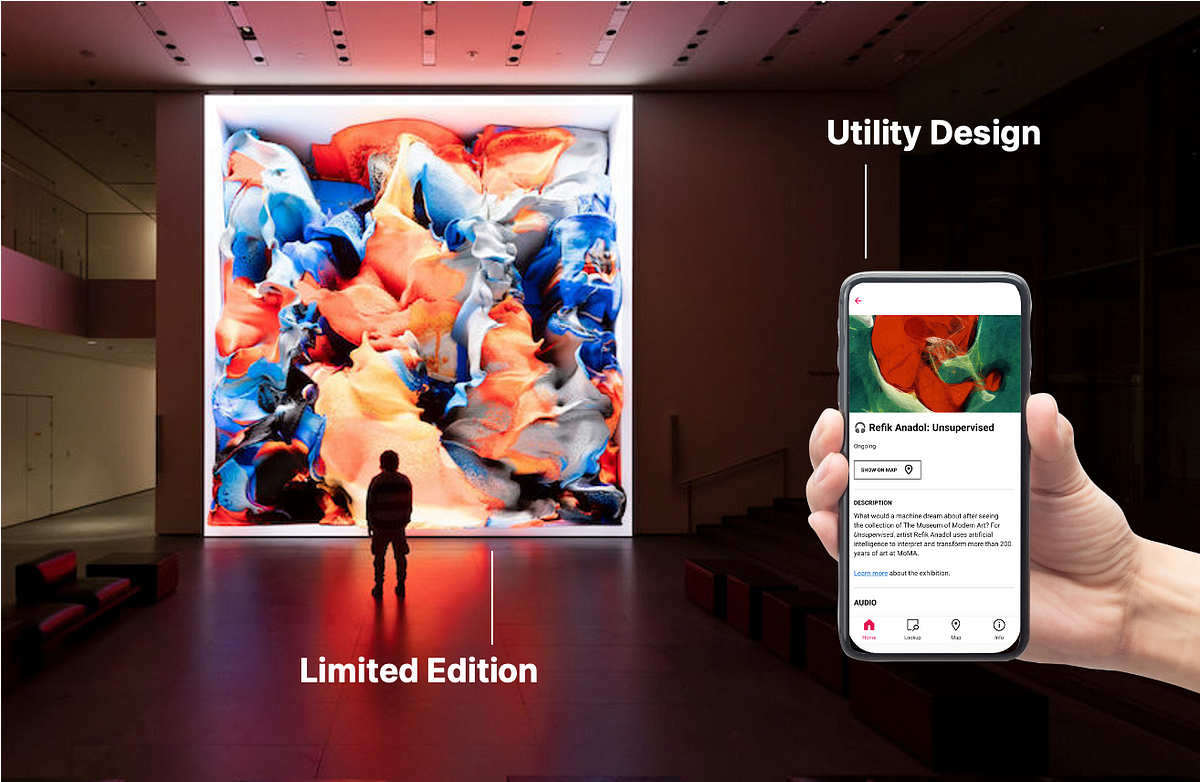

At this point, I would like to clarify that design shouldn’t be seen as a broad category of people. No doubt design thinkers play an important role in making quicker decisions as a team, but we must recognise the technical toolset (not skillset or mindset) of mainstream designers. They aren’t marketing or business people turned design evangelists, but practitioners who have chosen to spend their 10,000 hours purely on making something more usable and beautiful. They are diverse in talent, ranging from coding to digital sculpting to animation. Their evidence is seen on every physical, service, or digital product, provided it was given to a skilled designer in the first place.

Sadly, business folks can’t see this value, and it is partly the designer’s fault. This is because the two users have not addressed the elephant in the room: that the two disciplines, business and design, aren’t the same thing. A few artefacts from the business world will prove the point. As a designer, when was the last time you looked at

- balance sheets?

- investor factsheets?

- stock charts?

- annual reports?

- memorandum of understandings (MOU)?

- business cases?

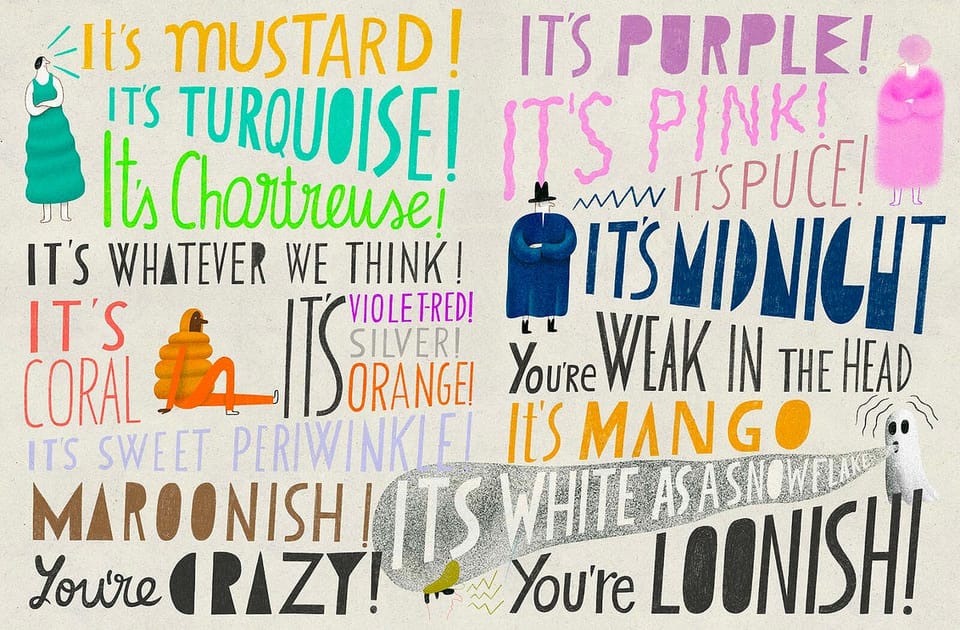

Chances are the client or business representatives have not fully understood the value of design artefacts either, other than knowing the difference between UI and UX. But ultimately, numbers and profits govern an organisation. Designers are thus left to justify the value they bring but find it challenging when they can't navigate through a storm of business jargon (e.g., ROI, CAGR, CAC).

So while the business world was introduced to design thinking, the reverse is also true. Has the design world embraced business thinking?

The bad

Yes, there has been resistance in the design community. Some pious designers might even call it taboo, shunning it completely and sticking to design fundamentals. Additionally, despite understanding that business is a crucial set of knowledge, it is uncommon to find it fitting in design education.

Look across design schools and design bootcamps. You’ll see that there aren’t many examples of blended applications, unless a professor chooses to do this as part of their research. Instead, what we see is a bland mixture of design methods prescribed as formulas. Formulas that need updating in a new business setting. No wonder designers can’t defend themselves among business peers and leaders in their organisation. They are going around in the wrong loop.

Then again, there are some designers who decide to take the less-trodden path, wandering into this space of business and design:

I was at a crossroads during the early days of my design career. I recall being involved in a design exhibition held at a local museum, which showcased works done by veteran designers. They carried years of experience, some of them in reputable multinational corporations (MNCs). Others were respected individuals from design agencies. As a small fish in their big pond, I was actually tasked with taking care of the exhibition by explaining the works to passersby. It wasn’t a glorious task, but I had the chance to speak to some of the design veterans.

There was one particular day that I will never forget. I had a chance to intimately speak to a seasoned industrial designer turned artist. As we idled the time away at the design exhibition, I came to learn that he was one of the first designers in Singapore to hold a masters in design from a prestigious overseas design school. From his technical knowledge of his design showpiece and the way he spoke, I could tell he had a high level of design maturity. Naturally, my admiration led me to ask for his opinion about following the same path. Should I follow in his footsteps and advance in design?

His words to me were rather surprising. Although he would recommend anyone take an advanced degree, he regretted taking up an advanced degree in design, citing it as a “waste of time.” The advice he would have given his younger self was to pursue a different degree besides what he already knew. The struggles after graduation were what eventually led him to the world of the arts.

Thus, that conversation created a life-altering journey for me as I made my way into a business school pursuing a masters degree specialising in innovation, entrepreneurship, and management. It was a unique experience where I had the privilege to make new friends with non-designers. It was also a gruelling task to pick up concepts on accounting, business economics, entrepreneurship, innovation management, venture capitalist modelling, and the list goes on. I wasn’t a student with distinctions, but neither was I flunking my subjects (other than accounting, which I dreaded the most. Sorry, mum)

And now, the Good

Through it all, after more than 10 years, I am still applying what I learned in school to my work to this day. And design continues to flow in that work. In fact, design startup founders such as Brian Chesky, Evans Sharp, Dylan Field, Felix Lee, and Melanie Perkins are more famous examples that are bound to apply business thinking and managerial techniques due to their titles as CEOs. They are shining examples for the design community on how to integrate two worlds together.

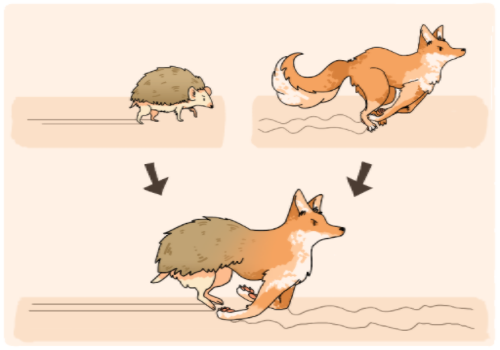

Which leads me to an even older story about a fox and a hedgehog. Although most of it is now lost with time, a sentence from the ancient Greek poet Archilochus still remains:

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

These woodland creatures went viral even before the Internet came about, inspiring many writings on leadership, forecasting, and even design. Philosopher Isaiah Berlin was responsible for providing more colour to the animals. In his essay, The Hedgehog and the Fox, he shared that hedgehogs “relate everything to a single central vision,” through which all that they say and do has significance. “Foxes, in contrast, “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way.”

Interestingly, these animals also exist in UX folklore. Originating from Jeremy Wilt’s article, the UX Fox represents designers who can apply expertise across several fields, such as psychology or business. They may also have taken an unconventional path, somehow ending up in the design community. Highly adaptable, they embrace uncertainty and typically wear researcher’s or facilitator’s hats.

Meanwhile, UX hedgehogs are specialists who have deep expertise in one area of design. Every one of us may have come across a profile that is exceptional in visual design or usability testing and has high levels of knowledge acquired over time.

Fears

Again, this concept needs updating in 2023. The trouble starts when teams are shrinking and UX/UI is in the late stages of transformation over the next few years. Being a UX Hedgehog in 2024 is becoming riskier with the advancements of AI GPT agents, especially as a UI designer doing visual design only. The same goes for UX designers, user researchers, or UX writers. Neither is UX Fox safe because, without any grounding, generative AIs are a lot quicker to generate ideas. The fox loses its competitive advantage over a larger language model.

Therefore, it is time for designers to step up and step out of designing as one big idea. We need to start thinking like design CEOs, where design matters in the P/L statements and to the stakeholders of the company.

And the best way to do that is to be a UX foxhog—a portmanteau of combining the foxy and spiky traits of the two woodland creatures.

Hopes

Because, why not? Say you are a UX hedgehog, and you know your role is at risk of obsolescence. A foxy behaviour would be to venture out to do something unconventional, like an online course on business, which is totally unrelated to design. The beauty of the foxhog is its cyclical return to hedgehog mode, where it will update its primary operating mode. And over time, by merging these two concepts together, a new business design innovation emerges. This is also the reason why many design CEOs have startup founders’ origins: they innovate a new way of working altogether.

A UX foxhog also thrives in the workplace. The foxy side adapts to the corporate environment, while the hedgehog stays centred on the values of the designers. More importantly, the UX foxhog is now able to participate in linking their activities with organisational impact.

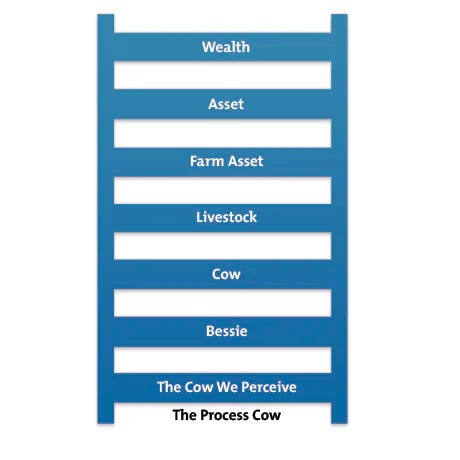

One such useful method is abstraction laddering: a framing tool created by S.I. Hayakawa. It proposes that the category of language be positioned at different rungs on a ladder, with the bottom rung being concrete language and the top being abstract language.

Below is Hayakawa’s “Bessie the cow” example to demonstrate this thinking of concrete and abstract.

- The Process Cow. The atoms, molecules and so on that the animal is made of.

- The Cow We Perceive. Not the word “cow,” but the object that we see. We’re already overlooking some detail, such as what she is actually made of.

- Bessie. The name we give to the perceived object. When we do this, we leave out more characteristics such as her color.

- Cow. When referring to Bessie as a cow, we use abstract characteristics that are common to all cows — not specifically to Bessie.

- Livestock. At this level of abstraction, we use the characteristics that Bessie shares with other farmyard animals to group her as livestock.

- Farm Asset. When we refer to Bessie as a farm asset, we look only at those characteristics that she shares with other valuable objects on the farm.

- Asset. The word “asset” takes Bessie from the farmyard context to a higher, wider level of abstraction where she is just one type of valuable resource. Few specific details about Bessie remain at this level of abstraction.

- Wealth. The highest level of abstraction, from which we learn almost nothing about Bessie.

Now imagine this: given we should be familiar with the design activities, the task is now to work up on the abstraction ladder by asking, ‘so what?’ Preferably asking the same question five times. If this strangely sounds like another technique known as ‘5 whys’, that is because the mechanism is similar but differs in direction. By asking, 'so what?’, you are understanding the importance and impact of the activity by attempting to address the abstract language.

For example:

Designer 1 (D1): I design the user experience of the check-in flow of an airline.

Designer 2 (D2): So what?

D1: Users will have a more seamless check-in experience without friction.

D2: So what?

D1: Users will save time by not waiting around. They will have more time to do other things.

D2: So what?

D1: More users will get to their boarding gate on time. They will have more time to get ready for boarding.

D2: So what?

D1: Planes can achieve better on-time performance and avoid paying penalties for potential delays.

D2: So what?

D1: The airline benefits from better reviews from customers and the airport, ensuring more revenue and more efficient cost management.

Dreams

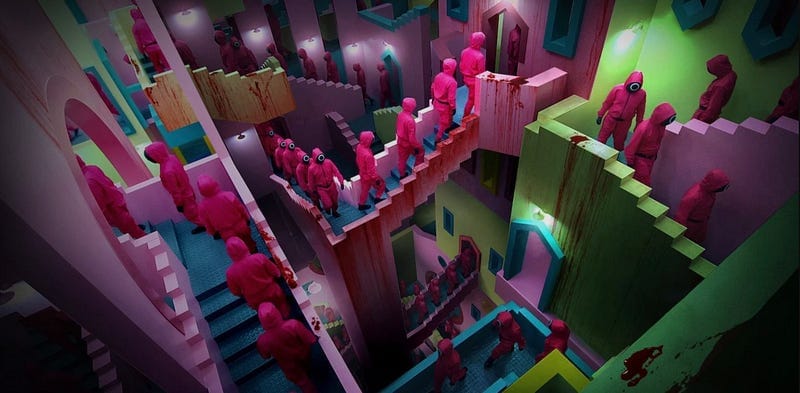

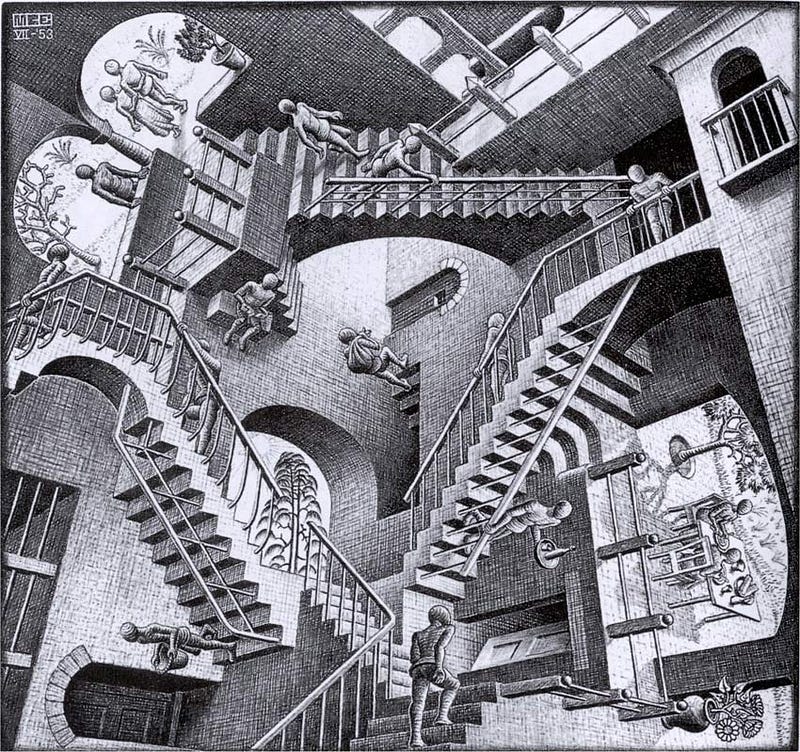

This one path could potentially branch out into multiple lanes, such as a pre-ordering or lounge experience. From there, newer flows can be created, leading to further details for the designer and his team. As the team climbs each rung of the ladder, so too does the relevance between business and design. Before you knew it, you had entered the realm of Escher’s staircases, Relativity.

And as a matter of fact, Escher’s staircase is precisely the vantage point of the UX foxhog or design CEO, where the idyllic scene can be seen in three different ways at the same time. The view is mesmerising, yet daunting to achieve.

I’ve always wondered whatever happened to those designs from the design exhibition that I manned in 2012. Today, finding them in the marketplace is impossible. A hint of their past can only be found in some old social feeds in a dying social media group. Although the intent was never to commercialise those designs, one can only wonder about the potential it could have given if design is not designed for design sake.

Conversely, the products from design CEOs allow me to work remotely on my Figma file at an AirBnB apartment while getting new ideas from Pinterest. The longevity and usefulness of design are evident in the business-thinking designers of today and the UX foxhogs of tomorrow. The question is not a matter of why, but a matter of when. When will you take your first step?

Perhaps 2024 is the year to climb as a new designer. If so, check out the available e-book, Business Thinking for Designers. Meanwhile, quoting the words of another famous designerish CEO,

Stay hungry, stay foolish.

References

Berlin, I. (1967). The hedgehog and the fox. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Braga, C., & Teixeira, F. (2023). The State of UX in 2024. UX Trends. https://trends.uxdesign.cc/2024

Gordon, A. (2023, December 4). Spotify to Axe 1,500 Jobs in Third Round of Layoffs in 2023. TIME. https://time.com/6342222/spotify-layoffs-1500-jobs/

Hayakawa, S. I. (1948). Language in action. Harcourt, Brace And Co.

MindTools. (n.d.). The Ladder of Abstraction. Www.mindtools.com. https://www.mindtools.com/aon6wso/the-ladder-of-abstraction

Rao, V. (2015, October 30). The Unholy Monster that turns Uncertainty into Certainty. Studio.ribbonfarm.com. https://studio.ribbonfarm.com/p/the-unholy-monster-that-turns-uncertainty

Rumsey, R. (2020). Business Thinking for Designers. https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/609ce44d3dfdab98b5019cf9/6143613a2ebbb44c1e9d1251_BusinessThinkingforDesigners.pdf

Wilson, M. (2023, November 3). Design giant Ideo cuts a third of staff and closes offices as the era of design thinking ends. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90976682/design-giant-ideo-cuts-a-third-of-staff-and-closes-offices-as-the-era-of-design-thinking-ends

Wilt, J. (2015, October 5). Unicorns, Foxes, and Hedgehogs: Why You Need Diversity on Your UX Team :: UXmatters. Www.uxmatters.com. https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2015/10/unicorns-foxes-and-hedgehogs-why-you-need-diversity-on-your-ux-team.php